Ever since Leonard Koren introduced the Japanese concept of “wabi-sabi” to the West in his seminal book “Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers,” the idea of wabi-sabi has become commonplace in artistic circles. While its wider acceptance in the world is a good thing, it has also become overused and often misunderstood. Here is the latest installment in my 2-minute Japanese Artistic Concept video series:

Wabi-sabi is one of the artistic concepts I introduce in my class Sunday Night is Photo Night, and it presents a challenge for any photographer. Here is my attempt to explain this in terms that we as photographers can understand.

Enlightened hand of Buddha, ©2019 George Nobechi

Wabi-sabi is a deeply ingrained part of Japanese aesthetics. It is subconsciously recognized and is generally not commented on out loud. Japanese people do not say, “That’s very wabi-sabi.”

“Sabi” is the more accessible of the two words that together form the term. It comes from “sabiru” - and means to age, fade, wilt. It is visually tangible imperfection.

“Wabi” comes from “wabishii” - lamentation, loss, absence. It is an inward state.

Both terms may seem negative, but they are not. Through tea ceremony, ceramics, Zen practice and so on, the idea that these natural declines and changes that also trigger feelings in us are to be appreciated has become deeply ingrained in Japanese consciousness. If “sabi” refers to the fading and impermanence of things, wabi refers to our awareness and lamentation of them. Only together: the outwardly visible physical characteristics and the inwardly contemplative awareness - do we first experience wabi-sabi.

Teahouse and Garden, Kyoto ©George Nobechi

Wabi-sabi is often described as “rustic” or '“patina” in English, but these are only physical descriptors. They don’t go far enough to emphasize our feelings toward them. If you say “that looks very wabi-sabii,” then you probably mean it looks rustic or has patina. Don’t focus only on the visual elements and instead seek within yourself to see if they convey feelings of any kind to you about impermanence. Not every rusted, old thing is wabi-sabi.

Not everything traditional, old and Japanese conveys wabi-sabi by default. For example, look at the following two views of the famed stone garden at Ryoanji in Kyoto. The first frame feels wabi-sabi…the old wall, the lichen and growth and fading, and the brambles and branches above the wall. The second, with a sharp angle taken on the stones, does not feel wabi-sabi. We don’t have feelings of loss from them, even though it’s the same garden.

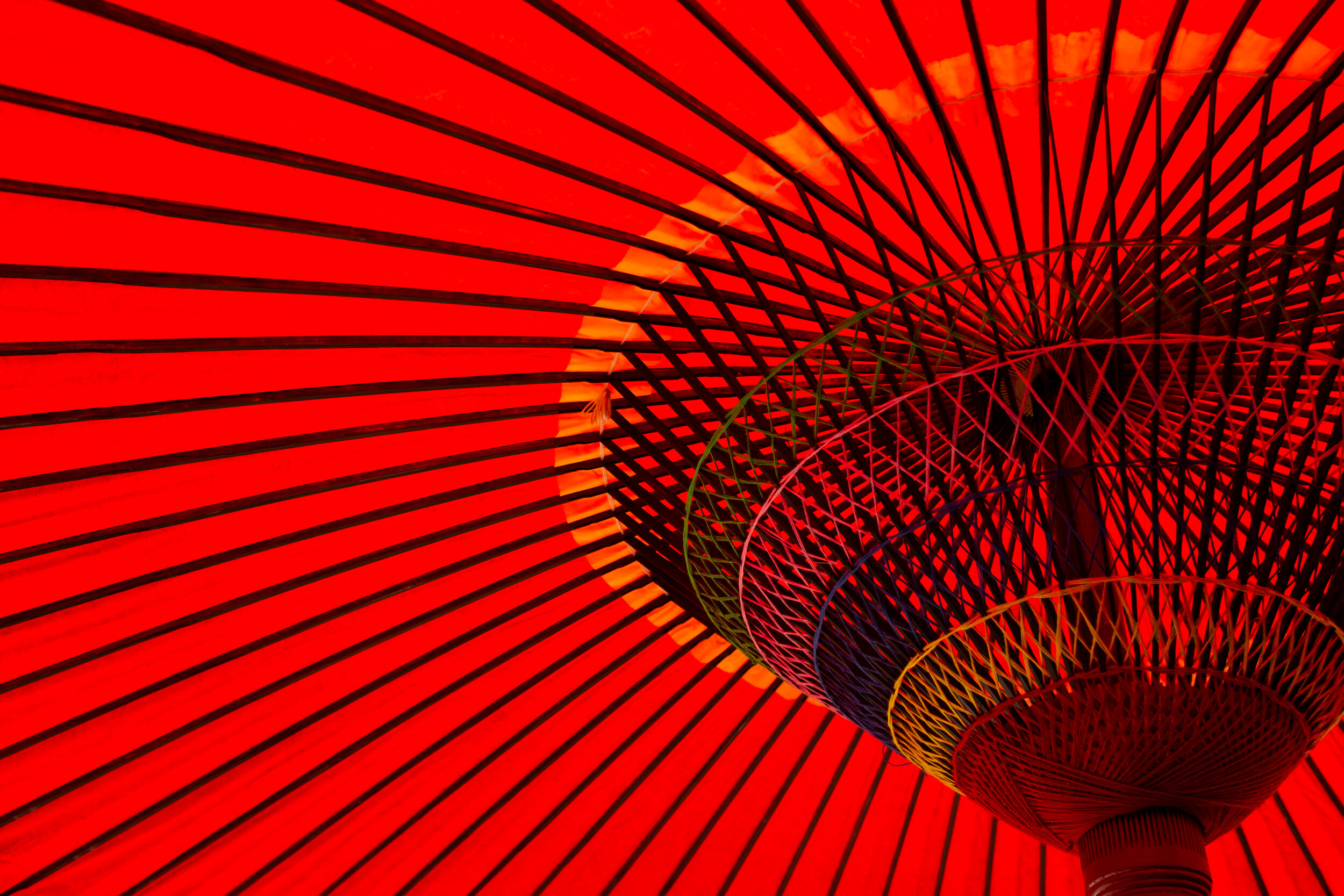

Or look at this handmade, traditional paper umbrella - the vibrance of the colors, the fine condition in which it has been kept - no feelings of wabi-sabi here. Nor is it present in the following photograph of a feudal castle.

Also, not everything that conveys feelings of wabi-sabi is found in Japan and not found in the West. See a sampling of these photographs made from different countries around the world.

When you incorporate wabi-sabi into your own practice, remember to not just focus on the visual, but become aware of what you feel as well.

Please read some of our other blog posts below. Thanks for reading!